A Crisis of Leadership Trust

The Crisis

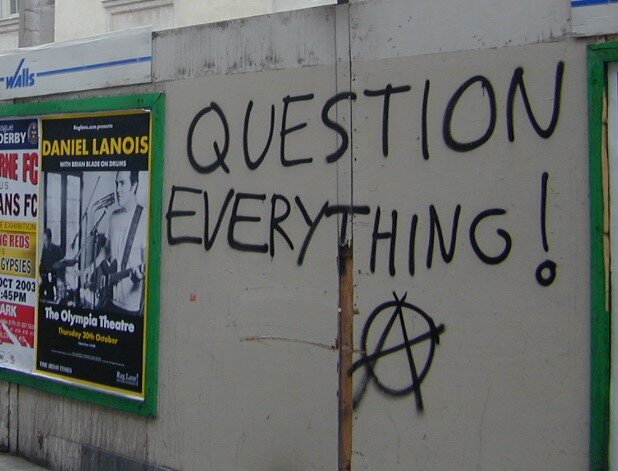

The times they are certainly a-changing, to paraphrase a certain ageing Nobel Prize-winning former hippy. Whether it’s the Coronavirus pandemic response, institutionalised discrimination, Facebook election interference, Brexit buses, MP’s expenses or dodgy dossiers about weapons of mass destruction, we collectively have an increasingly sceptical view of anything presented to us by people in positions of leadership.

In 1963 when Bob Dylan wrote The Times They Are a-Changing, he was 21 years old; the US were covertly increasing their presence in Vietnam, John F Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Martin Luther King gave his “I have a Dream” speech as millions demonstrated in support of racial equality, John Profumo resigned after lying to the UK parliament about his relationship with Christine Keeler and Hurricane Flora killed 8,000 people in the Caribbean, with the international response widely criticised.

Plus ça change? We can’t say it hasn’t been coming. This scepticism might well include you and it definitely includes me - certainly as a follower but chances are, also in the way people treat me as a leader. ‘Crisis’ is the only way to describe it.

What can you do about it?

Our leaders seem unable to inspire trust, but at least individually we can do something about our own trustworthiness. The seminal work of Maister, Green & Galford, (The Trusted Advisor, 2000) and Green & Howe (The Trusted Advisor Fieldbook, 2012) remains some of the best in relation to trust in a work context. I think it’s worth re-visiting given the times we find ourselves in and the challenges you may be facing as a leader.

The Trust Equation

Maister, Green and Galford created the Trust Equation to breakdown how the various elements of trust inter-relate:

T = C + R + I

S

Where:

T = Trustworthiness

C = Credibility

R = Reliability

I = Intimacy

S = Self-orientation

Credibility and Reliability can broadly be summarised as “know your stuff, been-there-done-that, show up on time and keep your promises”. Or more simply just “be professional”. In mature industries and in most modern organisations, you can usually take it largely for granted that leaders (you included) probably have plenty of this; there will be a recruitment and career progression process that makes sure only qualified and experienced people get into those roles and a performance management process that rewards delivery of tasks, targets, outcomes and results. Imposter Syndrome aside, you are probably doing fine here.

What differentiates effective leaders?

Especially when the times they are a-changing, leaders need to draw on more than just the task-based aspects of trust. As Maister, Green and Galford stated, “The most effective, as well as the most common, sources of differentiation in Trustworthiness come from Intimacy and Self-Orientation.”

Let’s be clear, intimacy does not mean a sharing of your most personal details, but it absolutely does mean engaging and sharing your emotions as they pertain to the issues at hand and the role you fulfil. Yes, you should maintain mutual respect and stay within appropriate boundaries, but you have to bring something of yourself (hopefully your “best self”) to your leadership to be your most effective.

Work, and especially the impact you have as a leader, is intensely personal and emotional. As a leader how can you possibly expect others to trust you and follow you if they don’t really know you as a person and how you feel? People follow people, not organisations and especially when times are uncertain it’s the more people-oriented aspects of Trustworthiness that need to be to the fore.

Self-Orientation, the last component of the equation, is the destroyer of Trustworthiness. Self-orientation is about more than pure self-interest – it’s about how much the other person feels the relationship is focused on your interests and objectives rather than theirs. Selfishness and greed are the most obvious forms of self-orientation, but there are many other more subtle signs: not asking questions; not appearing to actively listen; relating issues to how they impact you or “the organisation” (rather than seeking to understand the impact on the other person first); being defensive; not appearing to hear concerns and issues; not saying “I don’t know” when you don’t know; communicating in a style and language that suits you rather than the other person.

Conversely when I ask development programme participants to describe what it’s like being on the receiving end of a leader with low self-orientation, they describe a memorable, empowering experience – “They always had my back and I knew that”.

Are you a trustworthy leader?

A high level of Intimacy and a low level of Self-Orientation, especially in times of uncertainty, are critical to your success as a leader – ignore them at your peril.

When was the last time, unprompted, someone in your team told you how they really feel about work? What’s getting in the way of you being fully engaged, emotionally with those you are leading and being led by? What can you do to achieve your objectives whilst bringing others along with you?

If people think you are leading them with only your own interests to the fore or that you aren’t overtly concerned with their interests, it’s unlikely you will be able to develop a trust-based relationship. If that’s the case, whilst they may engage “functionally” with the tasks to be carried out, they will not engage emotionally or give all of themselves to the cause.

These uncertain times demand leaders that we can trust.